Decoding the Emotional Architecture of Elite Performance

„True victory begins long before the race — in the quiet mastery of mind, emotion, and self.“ – Erich Schimmel

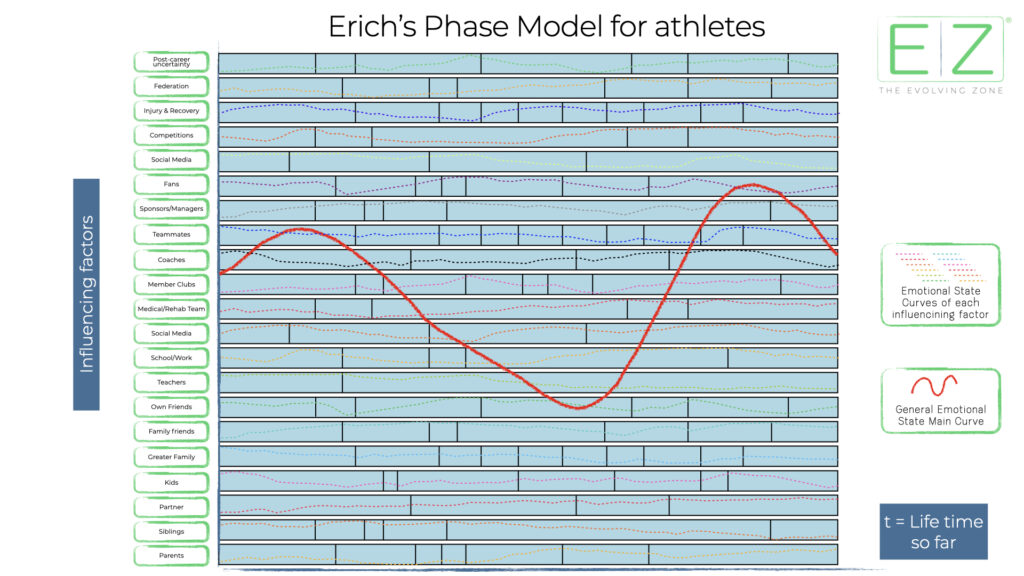

In the world of elite athletics, success is often measured in seconds, centimeters, or kilograms. Yet the real competition unfolds far from the eyes of spectators—within the mental and emotional landscape of the athlete. Every performance, whether record-breaking or heart-breaking, is preceded and followed by a cascade of emotional experiences. Training, competition, recovery, victory, injury, failure—each creates a distinct emotional wave. And within this complex terrain, Erich’s Phase Model emerges as an invaluable tool for understanding and navigating the emotional reality behind athletic excellence.

As introduced in previous TEZ blogs (I recommend you to read now the previous blog: “Erich’s Phase Model – The theory behind”), the Phase Model is founded on a profound truth: life unfolds in phases. These phases are not linear, nor are they strictly biological. Instead, they are dynamic, non-synchronized experiences shaped by emotional responses and contextual factors. For athletes, this insight becomes transformative. Because their environment is high-stakes, their timelines are compressed, and their identity is often fused with performance outcomes, recognizing and understanding their personal emotional curves becomes not just helpful—but essential.

In this sense, the model aligns seamlessly with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, which shows that human development occurs through interactions between an individual and their various environmental systems. These include the microsystem (e.g., coach, teammates, family), mesosystem (interactions between microsystems), exosystem (governing institutions, media), and macrosystem (cultural values, norms), all evolving over time within the chronosystem. For athletes, understanding which system is exerting pressure or support at any given time helps to decode emotional responses more clearly and apply tailored strategies.

A Personal Encounter: The Story of Leila

To make this more tangible, allow me to share the story of Leila. Just for complete disclosure of information, I have changed her name and age. For us here, Leila is 24, a professional track and field athlete. A fierce competitor with international experience, Leila had set her sights on the European Championships. However, six months before the qualifiers, she suffered a debilitating hamstring injury during a speed endurance session. It wasn’t just her physical condition that took a hit. Her confidence, identity, and emotional balance all entered a downward spiral.

When she came to me, her voice trembled with uncertainty: „I feel like I’m stuck in a tunnel. Everyone around me is training, qualifying, moving forward. And I’m here, stuck between ice packs and rehabilitation routines. I honestly do not know what to do!”

We began by applying Erich’s Phase Model to her situation. Not in theory, but in practice. We mapped out her influencing factors, rated their current emotional state, and visualized their individual curves. As the dots connected, a pattern emerged: while some areas like her support from physiotherapists and family were trending positively, other key factors such as coaching, sponsorship, and self-confidence were plunging.

What this model did for Leila was something no training manual or rehab program could offer—it gave her clarity, agency, and a structured understanding of her internal landscape. She stopped seeing herself as broken and started seeing herself as evolving within a phase.

The Athlete’s Emotional Ecosystem: Expanding the Model

“Se juega como se vive” – Francisco “Pacho” Maturana

Translated: “You play the game exactly the same way as you live your life”

Francisco “Pacho” Maturana’s player philosophy centered on empowering athletes to express their creativity within a structured tactical framework. He believed that football should be played with joy and intelligence, encouraging players to take ownership of their roles and make decisions on the field. The athlete as a system was part of that philosophy.

The athlete’s system is far more complex than the system of other humans. Therefore, beyond the core elements of my original Phase Model, the athlete’s world includes high-intensity influencing factors that shape both their performance and well-being. Let’s expand on each one and see what are the potential positive and negative influence they can exercise and some hints about what the athlete can do proactively:

- Coach and Coaching Staff

Positive impact: A strong, trust-based relationship with the coach creates emotional stability, tactical clarity, and personal motivation. It serves as a pillar in moments of uncertainty. Negative impact: Miscommunication, mismatch in values, or inconsistent feedback can erode confidence and disrupt the emotional curve. What to do: Athletes can build regular communication rituals, clarify expectations early on, and engage in feedback dialogues that create mutual understanding. Communication is key here and we could have a complete training just around this and by the way each of the topics, but we will let it for the moment be. - Teammates and Training Partners

Positive impact: A supportive team fosters belonging, shared effort, and motivation. Training partners who challenge respectfully elevate performance. Negative impact: Rivalry, jealousy, or social exclusion can create emotional isolation and disrupt team dynamics. What to do: Athletes should invest in emotional intelligence training, practice open dialogue, and set shared goals with teammates to shift from competition to collaboration. - Sponsors and Managers

Positive impact: Financial backing and professional guidance ease pressure and enable focus on performance. Negative impact: High expectations, branding pressure, or transactional relationships can strain authenticity and motivation. What to do: Athletes can set clear boundaries, align sponsorships with personal values, and work with mentors or agents who prioritize long-term well-being. - Fans and Social Media

Positive impact: Fan support can provide encouragement, increase visibility, and amplify pride in progress. Negative impact: Negative comments, online harassment, or comparison to others can damage self-esteem. What to do: Athletes can curate their social media feed, set usage limits, and shift focus to personal milestones rather than public approval. - Medical and Rehab Team

Positive impact: Competent, empathetic support during injury builds trust and reduces anxiety. Regular progress checks maintain hope. Negative impact: Poor communication or impersonal care can intensify frustration, prolong recovery, and lead to fear of reinjury. What to do: Athletes can proactively ask questions, request clarity in rehab plans, and seek second opinions when needed to maintain agency. - Competition Calendar

Positive impact: Structure, goals, and rhythm enhance focus and build anticipation. Planning peaks helps align training and motivation. Negative impact: Overload, lack of recovery time, or missed events due to injury can lead to disappointment and fatigue. What to do: Athletes should learn to mentally reframe missed competitions, schedule downtime, and define purpose beyond the event itself. - Injury and Recovery

Positive impact: Recovery phases can foster self-reflection, growth in other areas, and recalibration of goals. Negative impact: Isolation, fear, and loss of identity are common. Reinjury fear can stunt progress. What to do: Journaling, guided visualization, and connecting with others who’ve recovered successfully can restore mental strength. - Sporting Federation / Club Structure

Positive impact: Clear pathways, resource access, and fair evaluation fuel ambition and security. Negative impact: Political decisions, favoritism, or lack of communication can breed uncertainty and disillusionment. What to do: Athletes can document their progress, communicate proactively, and engage with player associations or athlete support systems. - Post-Career Uncertainty

Positive impact: Planning ahead can foster identity expansion, financial security, and purpose beyond sport. Negative impact: Fear of irrelevance, loss of structure, and emotional void are common for unprepared athletes. What to do: Exploring hobbies, building professional networks, and investing in education or mentorship programs while still competing provides grounding.

Each of these factors carries its own emotional trajectory. Awareness of them—not just cognitively, but in real-time emotional tracking (being in the NOW)—can empower athletes to intervene early, reframe challenges, and strengthen their main curve.

These factors each have their own emotional trajectory. The beauty of the model is in recognizing that these trajectories are not synchronized. One curve might be rising while another goes down. Emotional balance doesn’t come from perfection in all areas, but from awareness and intentional regulation.

Importantly, these influencing factors also mirror the four core psychological domains identified by Rocío Pomares, Head of High-Performance Psychology at FC Barcelona. According to her:

- Emotional stability reflects how well athletes manage frustration and self-regulate under pressure—essential for maintaining a stable main curve.

- Inner force represents motivation, perseverance, and the willingness to make sacrifices for long-term goals.

- Adaptation ability includes flexibility, humility, and the capacity to embrace different roles or contexts.

- Competitive development reflects the ability to channel training into performance, especially under pressure.

Pomares emphasizes the centrality of self-knowledge, asserting: „Only if the players know themselves and how they work, they will be able to manage themselves.“ This statement perfectly mirrors the purpose of the Phase Model—to foster self-awareness through mapping and reflecting on emotional dynamics.

Moreover, Pomares categorizes environments not as „positive or negative“ but as useful or not useful, a distinction that resonates with our approach to evaluating emotional curves. A seemingly supportive family can create undue pressure, while a less structured background may foster resilience and drive. This echoes Bronfenbrenner’s understanding that the same system can produce different developmental outcomes based on timing, context, and individual interaction.

Coaching Insight: Surfing the Emotional Main Curve

The Phase Model shows that all influencing factors feed into a main emotional curve. If too many factors trend downward, the general emotional state drops, increasing risk of burnout, anxiety, or self-doubt. However, just as in sports, we can train the mind to respond.

We introduced a simple practice into Leila’s daily routine:

- Emotional check-ins („What phase am I in today?“)

- Support network mapping („Who uplifts me right now?“)

- Reframing exercises („What is this phase trying to teach me?“)

With time, she began to see each phase as a training ground, not a verdict. Her injury was not an end, but a transition into a phase of self-mastery, patience, and reflection.

The power of resilience, as also described by Pomares, lies in the ability to transform negative emotional input into focused, high-intensity output. That transformation starts with awareness—and the Phase Model provides the structure to achieve it.

The Power of Fun and Identity Beyond Performance

One essential insight from the model is often overlooked in high-performance sports: fun is not a luxury. It is fuel.

Fun lifts the emotional curve. It resets tension, revitalizes motivation, and grounds the athlete in the present moment. Too often, high-achieving athletes become entangled in expectations and outcomes, losing sight of the joy that first brought them into the sport. When play becomes only pressure, the emotional cost rises.

Reintroducing fun acts like an emotional reset button. It connects athletes with their intrinsic motivation and helps reframe performance as expression rather than execution. Fun doesn’t mean a lack of seriousness—it means renewal. It reminds athletes they are more than their rankings, times, or statistics.

For Leila, it was rediscovering dance. She began using movement as joy, not just discipline. Her confidence returned not from winning, but from laughing. This was resilience in motion.

For others, fun might emerge through music, shared meals with teammates, or spontaneous games. Whatever form it takes, it’s a vital emotional nutrient in a world that often demands perfection. Coaches and athletes alike should protect time and space for fun—not just as a relief, but as a strategy for long-term performance and well-being.

From Phases to Flow

Every athlete goes through micro-phases within a season, and macro-phases across a career. By using the Phase Model, we shift the narrative from „I am broken“ to „I am in a phase.“ This mental reframe creates space for growth, for vulnerability, and for planning.

This aligns with Pomares‘ conviction that youth is the decisive period for shaping not just performance habits but identity. „The younger they are, the more malleable,“ she says. That mirrors the Phase Model’s belief that early emotional curve awareness can strengthen long-term resilience and growth.

When you understand your emotional landscape, you don’t just perform better. You live better.

So whether you are on the podium, recovering from injury, or staring at your next goal: pause, map your curves, and see what phase you are in. Use your highs to prepare, and your lows to listen. There is always movement. And there is always another phase.

Let’s evolve together.

Erich is an experienced life + business coach. He has a track record of over 21 years in supporting staff and leadership in organizations, athletes, and private people in their efforts to enable changes in their lives.

He knows from his own experience how to ignite the passion in people, how to let people gain new perspectives, set new objectives, and follow through completion.

As a native speaker, Erich provides coaching in German and Spanish, as well as in English thanks to his more than 3 decades of experience working at the international level.

Last posts

-

Erich’s Phase Model and the High-Performing Athlete

Elite performance isn’t just built in the gym—it’s shaped by the emotional systems surrounding the athlete. In this powerful blog, Erich Schimmel expands his Phase Model to the world of high-performance sports, offering athletes, coaches, and support teams a clear framework to understand emotional phases, internal resilience, and systemic influence. With real-life examples, references to…

-

Erich´s Phase Model – The Theory Behind

Navigating Life’s Phases with Clarity and Resilience This blog explores Erich’s Phase Model, a framework designed to help individuals navigate the natural phases of life with a deeper understanding of resilience, adaptability, and self-reflection. Life is ever-changing, and recognizing the transient nature of each phase enables us to harness positive moments and endure challenges effectively.…

-

Resilience – A Tool to Transform Adversity into Growth

Discover how resilience can transform adversity into growth. This article explores Erich’s Phase Model and practical strategies like self-affirmation, MACARENA mental training, and continuous learning to navigate life’s challenges. Highlighting insights from renowned studies, including Falk et al.’s work on self-affirmation, the piece emphasizes the importance of adaptability, community support, and the cyclical nature of…

Mit Stolz präsentiert von WordPress